Table of contents

Chapter-1

- Why study metric spaces

- What is a metric space

- Examples of metric space

- 1.1 - Problems

- 1.2-3 $\ell^p$ space and important inequalities

- 1.2 - Problems

- 1.3 Open sets, Closed sets, Neighbourhoods

- Examples of separable metric spaces

- 1.4 - Convergence, Cauchy Sequences, Completeness

Chapter-1 Metric Spaces

Why study metric spaces?

A set like a bag of items has no structure in and of itself. The only things it boasts of is having the intuitive primitive notion of containing things and certain other peculiar axioms (ZF Axioms). To study richer objects in abstract math, we have to start adding other axioms (assumptions) to our sets in order to impose a structure on these objects. These enable us to prove beautiful theorems about these abstract objects which may have various concrete realizations. This theme of stripping away unnecessary specifics is quite common in abstract mathematics.

What is a metric space?

A metric space is a step in this direction.

A

metric space is a set $X$ along with a mapping $d: X \times X \to \mathbb{R}$ such that:

- $d(x,y) \geq 0$ for all $x,y \in X$

- $d(x,y) = 0$ iff $x = y$

- $d(x,y) = d(y,x)$ for all $x,y \in X$

- $d(x,y) + d(y,z) \geq d(x,z)$ for all $x,y,z \in X$

Examples of metric spaces:

- The set of real numbers $\mathbb{R}$ with metric $d(x,y) = |x-y|$

- The 2D plane of real points $\mathbb{R}^2$ with $d((x_1,x_2),(y_1,y_2)) = \sqrt{((x_1-x_2)^2 + (y_1 - y_2)^2)}$

- Function space $C[a,b]$. Let $X$ be the set of all real-valued functions defined and continuous on $J = [a,b]$. Let $d(x,y) = \max_{t \in J}|x(t)-y(t)|$. This is a metric space where each point is a function.

- Discrete metric. Let $X$ be any set. Let $d$ be a metric defined as follows $d(x,x) = 1$ and $d(x,y) = 0$ for $x \neq y$ given $x,y \in X$. This is the discrete metric space and is often useful in giving counterexamples to disprove statements.

1.1 - Selected problems

Show that the real line is a metric space

The first three axioms of a metric are immediate. The triangle inequality can be seen with the following $|a + b| \leq |a| + |b|$, or $|x-y| + |y-z| \geq |x-z|$

Does $d(x, y) = (x - y)^2$ define a metric on the set of all real numbers?

No, take $x = 0, y = 0.5$ and $z = 1$. Then $(x-y)^2 + (y-z)^2 = 0.25 + 0.25 = 0.5 < 1 = (x-z)^2$

Show that $d(x, y) = \sqrt{|x - y|}$ defines a metric on the set of all real numbers.

Again the first three axioms are immediate. For the last one: $$ \begin{align} \bigg(\sqrt{|x-y|} + \sqrt{|y-z|}\bigg)^2 &= |x-y| + |y-z| + 2\sqrt{|x-y|}\sqrt{|y-z|}\\ &\geq |x-z| + 2\sqrt{|x-y|}\sqrt{|y-z|}\\ &\geq |x-z|\\ &= \bigg(\sqrt{|x-z|}\bigg)^2 \end{align} $$

Find all metrics on a set $X$ consisting of two points. Consisting of one point

If a set consists of only two points then the triangle inequality is automatically true. Therefore any non-negative real function $d(x,y)$ with $d(x,y) = d(y,x)$ and $d(x,x) = 0$ is a valid metric. If the set contains only one point, then we only need a metric with $d(x,x) = 0$.

Let $d$ be a metric on $X$. Determine all constants $k$ such that (i) $kd$, (ii) $d + k$ is a metric on $X$

- We know that a metric must be non-negative. Hence $k \geq 0$. Apart from this if $x = y$, then $k d(x,y) = 0$ as well. But for the converse to be true, i.e. $d(x,y) = 0 \implies x = y$, $k > 0$. The third and fourth axiom will hold true even after multiplying the metric function with a positive constant.

- Note that here if $ x = y$, then $d'(x,y) = d(x,y) + k = k$. Hence the only possible value of $k$ here is zero.

1.2-3 $\ell^p$ space and important inequalities

Among others interesting examples of metric spaces, an important one is the $\ell^p$ space of which Hilbert’s sequence space ($\ell^2$) is a special case. Showing that it is indeed a metric space will use two beautiful inequalities : Hölder’s inequality and Minkowski’s inequality. But first we define the space.

Let $p \geq 1$ be a real number. The space $\ell^p$ is defined as the set of all sequences $x = \{\alpha_i\}$ of complex numbers (possibly real), such that $\big(\sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i|^p \big)$ converges along with the metric $$ d(x,y) = \big(\sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i - \beta_i|^p\big)^{(1/p)} $$ with $x = \{\alpha_i\}$ and $ y = \{\beta_i\}$.

As a special case for $p=2$ we get the Hilbert sequence space ($\ell^2$) with metric:

$$ d(x,y) = \big(\sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i - \beta_i|^2\big)^{(1/2)} $$

We now want to show that metric defined above is indeed valid. We trace the outline of the proof with stating all major results. The full proof can be found in the book.

Let $p > 1$ and $q$ be such that: $$ \frac{1}{p} + \frac{1}{q} = 1 $$ Then $p$ and $q$ are called conjugate exponents.

The above definition implies that $p+q = pq$ and thus $(p-1)(q-1) = 1$

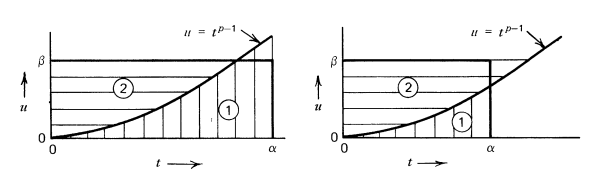

Let $\alpha, \beta$ be positive reals and $p,q \in (1,\infty)$ be conjugate exponents. Then $$ \alpha \beta \leq \int_0^\alpha t^{p-1} dt + \int_0^\beta u^{q-1} du = \frac{\alpha^p}{p} + \frac{\beta^q}{q} $$

Though a formal proof is omitted, it can be visually seen in the following figure taken from the book by comparing the areas of the rectangle and the two integrals.

Interestingly, equality holds when:

$$ \beta = \alpha^{p-1} $$

Hölder's inequality

Let $ x = \{\alpha_i\}$ and $y = \{\beta_i\}$ be two sequences in $\ell^p$ and $\ell^q$ space respectively, where $p,q \in [1, \infty)$ are conjugate exponents. Then $$ \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i \beta_i| \leq \big( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i|^p \big)^{1/p} \big( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\beta_i|^q \big)^{1/q} $$

First, for some conjugate exponents $p,q$, let $ \tilde{x} = \{\tilde{\alpha}_i\} \in \ell^p$ and $ \tilde{y} = \{\tilde{\beta}_i\} \in \ell^q$ be sequences such that: $$ \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\tilde{\alpha}_i|^p = 1 \quad \text{ and } \quad \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\tilde{\beta}_i|^q = 1 $$ Then using the previous theorem, for each $i$ we have: $$ |\tilde{\alpha}_i \tilde{\beta}_i| \leq \frac{|\tilde{\alpha}_i|^p}{p} + \frac{|\tilde{\beta}_i|^q}{q} $$ Summing for all $i$ till some fixed $n$, we get: $$ \begin{align} \sum_{i=1}^n |\tilde{\alpha}_i \tilde{\beta}_i| &\leq \frac{1}{p} \sum_{i=1}^n |\tilde{\alpha}_i|^p + \frac{1}{q} \sum_{i=1}^n |\tilde{\beta}_i|^q \\ &\leq \frac{1}{p} \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\tilde{\alpha}_i|^p + \frac{1}{q} \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\tilde{\beta}_i|^q \\ &= \frac{1}{p} + \frac{1}{q} \\ &= 1 \end{align} $$ Now we have for any $n$: $$ \sum_{i=1}^n |\tilde{\alpha}_i \tilde{\beta}_i| \leq 1 $$ This makes the sequence $\xi_n = \sum_{i=1}^n |\tilde{\alpha}_i \tilde{\beta}_i|$ monotone and bounded. Hence, we may infer that it is convergent. Furthermore $$ \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\tilde{\alpha}_i \tilde{\beta}_i| \leq 1 $$ Now given any sequences $x = \{\alpha_i\}$ and $y = \{\beta_i\}$ in $\ell^p$ and $\ell^q$ space respectively, define $\tilde{x} = \{\tilde{\alpha}_i\}$ and $\tilde{y} = \{\tilde{\beta}_i\}$ as follows: $$ \tilde{\alpha}_i = \frac{\alpha_i}{\big(\sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i|^p \big)^{1/p}} \quad \text{ and } \quad \tilde{\beta}_i = \frac{\beta_i}{\big(\sum_{i=1}^\infty |\beta_i|^q \big)^{1/q}} $$ After this transformation, the infinite sums of both $\tilde{x}$ and $\tilde{y}$ equal to one, and thus we may conclude that: $$ \begin{align} \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\tilde{\alpha}_i \tilde{\beta}_i| = \sum_{i=1}^\infty\frac{|\alpha_i||\beta_i|}{\big(\sum_{j=1}^\infty |\alpha_j|^p \big)^{1/p} \big(\sum_{j=1}^\infty |\beta_j|^q \big)^{1/q}} \leq 1 \end{align} $$ Hence, we get: $$ \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i \beta_i| \leq \big( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i|^p \big)^{1/p} \big( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\beta_i|^q \big)^{1/q} $$

Minkowski's inequality

Let $ x = \{\alpha_i\}$ and $y = \{\beta_i\}$ be two sequences in $\ell^p$ space. Then $$ \big(\sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i + \beta_i|^p\big)^{1/p} \leq \big(\sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i|^p\big)^{1/p} + \big(\sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i|^q\big)^{1/q} $$

Let us define $\omega_i = \alpha_i + \beta_i$. Then using the traingle inequality we get: $$ \begin{align} |\omega_i|^p &= |\alpha_i + \beta_i||\omega_i|^{p-1} \\ &\leq |\alpha_i||\omega_i|^{p-1} + |\beta_i||\omega_i|^{p-1} \end{align} $$ Hence summing it over all $i$ till some fixed $n$, we have: $$ \sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i|^p \leq \underbrace{\sum_{i=1}^n |\alpha_i||\omega_i|^{p-1}}_{\text{(I)}} + \underbrace{\sum_{i=1}^n |\beta_i||\omega_i|^{p-1}}_{\text{(II)}} $$ First, let's consider Term-(I). It is a series of product of two terms namely $|\alpha_i|$ and $|\omega_i|^{p-1}$. Though both $\sum_{i=1}^n |\alpha_i|$ and $\sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i|^{p-1}$ are finite sequences, we may extend them to be infinite by making terms $i>n$ to be zero. As both have only finite number of non-zero terms, they will both be in $\ell^p$. Now, we may use Hölder's inequality on Term-(I): $$ \begin{align} \sum_{i=1}^n |\alpha_i||\omega_i|^{p-1} &= \sum_{i=1}^n |\alpha_i \omega_i^{p-1}| \\ &\leq \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\alpha_i|^p \big)^{1/p} \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i^{p-1}|^q \big)^{1/q} \\ &\leq \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\alpha_i|^p \big)^{1/p} \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i|^{(p-1)q} \big)^{1/q} \\ &\leq \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\alpha_i|^p \big)^{1/p} \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i|^p \big)^{1/q} \quad [\text{because } (p-1)q = p] \end{align} $$ Similarly, we also get: $$ \sum_{i=1}^n |\beta_i||\omega_i|^{p-1} \leq \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\beta_i|^p \big)^{1/p} \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i|^p \big)^{1/q} $$ Now, we may simplify to get: $$ \begin{align} \sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i|^p &\leq \sum_{i=1}^n |\alpha_i||\omega_i|^{p-1} + \sum_{i=1}^n|\beta_i||\omega_i|^{p-1} \\ &\leq \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\alpha_i|^p \big)^{1/p} \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i|^p \big)^{1/q} + \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\beta_i|^p \big)^{1/p} \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i|^p \big)^{1/q} \\ &\leq \bigg( \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\alpha_i|^p \big)^{1/p} + \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\beta_i|^p \big)^{1/p} \bigg) \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i|^p \big)^{1/q} \end{align} $$ Hence $$ \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i|^p \big)^{1 - 1/q} = \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i|^p \big)^{1/p} \leq \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\alpha_i|^p \big)^{1/p} + \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\beta_i|^p \big)^{1/p} $$ This looks like we have almost obtained Minkowski's inequality but for some finite $n$. Now we may proceed as follows: $$ \begin{align} \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i|^p \big)^{1/p} &\leq \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\alpha_i|^p \big)^{1/p} + \big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\beta_i|^p \big)^{1/p} \\ &\leq \big( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i|^p \big)^{1/p} + \big( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\beta_i|^p \big)^{1/p} \end{align} $$ We know the rightside converges, and hence $\big( \sum_{i=1}^n |\omega_i|^p \big)^{1/p}$ is monotone and bounded. Hence we have $$ \big(\sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i + \beta_i|^p\big)^{1/p} \leq \big(\sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i|^p\big)^{1/p} + \big(\sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i|^q\big)^{1/q} $$

Recall that for the space $\ell^p$ we defined the metric as

$$ d(x,y) = \bigg( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i - \beta_i|^p \bigg)^{1/p} $$

First we may show that for $x = {\alpha_i}$ and $y = {\beta_i}$, $d(x,y)$ converges.

$$ \begin{align} d(x,y) &= \bigg( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i - \beta_i|^p \bigg)^{1/p}\\ &\leq \bigg( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i|^p \bigg)^{1/p} + \bigg( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |-\beta_i|^p \bigg)^{1/p}\\ &= \bigg( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i|^p \bigg)^{1/p} + \bigg( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\beta_i|^p \bigg)^{1/p}\\ &< \infty \end{align} $$

So the defined metric is indeed defined for all points in $\ell^p$. Now it is easy to see that properties (I),(II) and (III) hold. The triange inequality is also a direct consequence of Minkowski’s inequality. Let $x = {\alpha_i}$, $y = {\beta_i}$ and $z = {\gamma_i}$ be sequences in $\ell^p$.

$$ \begin{align} d(x,y) &= \bigg( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i - \beta_i|^p \bigg)^{1/p}\\ &= \bigg( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i - \gamma_i + \gamma_i - \beta_i|^p \bigg)^{1/p}\\ &\leq \bigg( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\alpha_i - \gamma_i|^p \bigg)^{1/p} + \bigg( \sum_{i=1}^\infty |\gamma_i - \beta_i|^p \bigg)^{1/p}\\ &= d(x,z) + d(z,y) \end{align} $$

So we have shown that $\ell^p$ is a valid metric space.

1.2 - Selected problems

Show that in 1.2-1 we can obtain another metric by replacing $1/2^j$ with $\mu_j > 0$ such that $\sum \mu_j$ converges

The metric used in 1.2-1 is $$ d(x,y) = \sum_{j=1}^\infty \frac{1}{2^j} \frac{|\alpha_j - \beta_j|}{1 + |\alpha_j - \beta_j|} $$ for $x = \{\alpha_i\}, y = \{\beta_i\}$ be any two complex sequences (maybe unbounded). The only thing to show is that by replacing $1/2^j$ with $\mu_j > 0$ such that $\sum \mu_j$ converges, we still get a valid metric. This requires us to show that such a metric will always converge for any two such sequences. The rest of the properties follow over nicely from 1.2-1. Accordingly, let us define the new metric as follows: $$ d'(x,y) = \sum_{j=1}^\infty \mu_j \frac{|\alpha_j - \beta_j|}{1 + |\alpha_j - \beta_j|} $$ such that $\mu_j > 0$ and $\sum \mu_j$ converges. Define $\xi_j$ to be the following sequence $$ \xi_j = \frac{|\alpha_j - \beta_j|}{1 + |\alpha_j - \beta_j|} $$ It is easy to see that $|\xi_j| \leq 1$ for all $j$. So our result reduces to the following theorem:

Let $\xi_j$ be a bounded sequence and $\sum_{j=1}^\infty \mu_j$ be a convergent sequence with $\mu_j > 0$. Then $\sum_{j=1}^\infty \mu_j \xi_j$ converges.

We show that $\sum_{j=1}^\infty \mu_j \xi_j$ converges absolutely which implies its convergence. Let $|\xi_j| \leq A$. Then for some fixed $n$ $$ \begin{align} \sum_{j=1}^n |\mu_j| |\xi_j| &\leq \sum_{j=1}^n A |\mu_j| \\ &= A \sum_{j=1}^n |\mu_j| \\ &\leq A \sum_{j=1}^\infty |\mu_j| \\ &< \infty \end{align} $$ Hence the sequence of partial sums $\sum_{j=1}^n |\mu_j \xi_j|$ is monotone and bounded, and thus $\sum_{j=1}^n \mu_j \xi_j$ is absolutely convergent.

Hence $d'(x,y)$ is defined for all sequences $x,y$. Rest properties can be proven similarly to 1.2-1.

Show that the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality implies that $$ (|\xi_1| + |\xi_2| + \ldots + |\xi_n|)^2 \leq n (|\xi_1|^2 + |\xi_2|^2 + \ldots + |\xi_n|^2) $$

The Cauchy-Schwarz inequality says that $$ \bigg( \sum_{i=1}^n |\xi_i \eta_i|\bigg)^2 \leq (\sum_{i=1}^n |\xi_i|^2)(\sum_{i=1}^n |\eta_i|^2) $$ Take $\eta_i = 1$ for all $i$.

Find a sequence which converges to 0, but is not in $\ell^p$ for any real $p \geq 1$.

Let $a_n = \frac{1}{\log(n+1)}$. It is clear that $a_n \to 0$. We claim that $x = \{a_n\}$ is not in $\ell^p$ for any $1 \leq p < \infty$. For this we must show that the following series diverges $$ \sum_{n=1}^\infty |a_n|^p = \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{1}{|\log(n+1)|^p} $$ We first observe that $a_n$ is a monotonically decreasing positive sequence. Applying the Cauchy condensation test, we may conclude that the convergence of the above is equivalent to convergence of $$ \sum_{k=0}^\infty 2^k |a_{2^k}|^p = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{2^k}{|\log(2^k+1)|^p} $$ Now $$ \begin{align} \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{2^k}{|\log(2^k+1)|^p} &\geq \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{2^k}{|\log(2^{k+1})|^p}\\ &= \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{2^k}{|(k+1)\log(2)|^p}\\ &= \frac{1}{|\log(2)|^p}\sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{2^k}{|(k+1)|^p}\\ \end{align} $$ We know that RHS diverges as the the exponential term on top grows faster than any polynomial.

Find a sequence $x$ which is in $\ell^p$ for $p > 1$ but $x \notin \ell^1$

Consider the series $x = \{a_n\}$ as $$ a_n = \frac{1}{n} $$ We know that $$ \sum_{n = 1}^\infty \frac{1}{n^p} $$ diverges for $p = 1$ but converges for $p > 1$. Hence we are done.

1.3 Open sets, Closed sets, Neighbourhood

Recap of some basic notions of Topology

Let $X$ be a metric space let $x \in X$. The neighbourhood of $x$ of radius $r > 0$ is defined as the set $$ N_r(x) = \{y \ | \ d(x,y) < r\} $$

A subset $M$ of a metric space $X$ is called open if every point of $M$ is an interior point meaning that for all $x \in M$ there exists an $r > 0$ such that $N_r(x) \subset M$.

Ideally we may define a closed set as one containing all its limit points.

A subset $M$ of a metric space $X$ is called closed if $M^c = X - M$ is open.

Now we may define a topological space

Let $X$ be a set let $\mathcal{T}$ be a collection of subsets of $X$. Then $(X , \mathcal{T})$ is called a

Topological Space if

- $\phi, X \in \mathcal{T}$

- Union of elements of $\mathcal{T}$ is in $\mathcal{T}$

- Finite intersections of elements of $\mathcal{T}$ is in $\mathcal{T}$

It is easy to see that if we take any metric space $X$ and let $\mathcal{T}$ be the set of all open sets in $X$, then $(X, \mathcal{T})$ is indeed a topological space.

Now we define the notion of continuity on a metric space.

Let $(X, d_X)$ and $(Y, d_Y)$ be two metric spaces and let $f: X \to Y$ be a mapping. We say that $f$ is continuous at $x_0 \in X$ if for all $\epsilon >0$, there exists a $\delta > 0$ such that for all $x$ such that $d_X(x,x_0) < \delta$: $$ d_Y(f(x), f(x_0)) < \epsilon $$

A convinient characterization of continuity is the following theorem given without proof

Let $(X, d_X)$ and $(Y, d_Y)$ be two metric spaces and let $f: X \to Y$ be a mapping. Then $f$ is continuous if and only if the inverse image of any open set in $Y$ is open in $X$.

There are two more important definitions to keep in mind

Let $M$ be a subset of a metric space $X$. Then $x_0 \in X$ (not necessarily in $M$) is called a limit point of $M$ if every neighbourhood of $x_0$ contains a point $x \in M$ such that $m \neq x_0$.

Let $M$ be a subset of a metric space $X$. Let $M'$ be the set of all limits of $M$. Then closure of $M$ (written as $\overline{M}$) is defined as $$ \overline{M} = M \cup M' $$

This allows us to define two more important notions, namely a dense set and a separable set.

A subset $M$ of a metric space $X$ is called dense in $X$ if $$ \overline{M} = X $$

A metric space $X$ is called separable if a countable subset $M$ of $X$ is dense in $X$.

Examples of separable and non-separable metric spaces

- Real numbers : The rational numbers are dense in $\mathbb{R}$ and they are countable. Hence $\mathbb{R}$ is separable

- Complex numbers : Consider the set of complex numbers whose real and imaginary parts are rational. They are dense in $\mathbb{C}$ as a consequence of the above. And we know that $\mathbb{Q}^2$ is countable. Hence $\mathbb{C}$ is separable

- Discrete metric space : Let $X$ be a set with the discrete metric. First observe that any proper subset $M$ of $X$ cannot have a limit point in $X \setminus M$, because for all $m \in M$ and $x \in X \setminus M$, $d(m,x) = 1$, and hence any neighbourhood of $x$ smaller than $1$ contains no $m \in M$. Thus $X$ is separable if and only if $X$ is countable itself.

The separability of $\ell^\infty$ and $\ell^p$ requires further discussion.

The space $\ell^\infty$ of bounded sequences with metric $$ d(x,y) = \sup_{n \in \mathbb{N}} |x_n - y_n| $$ is non-separable

The space $\ell^p$ of sequences $x$ such that $ \sum_{n=1}^\infty |x_n|^p < \infty $ along with metric $$ d(x,y) = \sum_{n=1}^\infty |x_n - y_n|^p $$ is separable

1.4 Convergence, Cauchy Sequences, Completeness

A recap of baby Rudin

A sequence $(x_n)$ in a metric space $(X,d)$ is called convergent if there exists an $x_0 \in X$ such that $\lim_{n \to \infty} d(x_n, x_0) = 0$

It is easy to show that a convergent sequence is always bounded. Now we define a Cauchy sequence

A sequence $(x_n)$ in a metric space $(X,d)$ is called a Cauchy sequence if for every $\epsilon > 0$ there exists an $N \in \mathbb{N}$ such that for $m,n > N$ $$ d(x_m,x_n) < \epsilon $$

It is worth thinking why this extra notion of a Cauchy sequence is needed. With the original definition of convergence, we must have a guess of the limit of a sequence in order to prove that it indeed converges as the definition requires it. But in some spaces, we have the nice property that every Cauchy sequence converges and as per the definition of a Cauchy sequence, we don’t require the knowledge of any limiting value which greatly aids in proving convergence in such scenarios.

With this we have the definition of a complete metric space

A metric space $(X,d)$ is called complete if every Cauchy sequences in $X$ converges.

It is important to note that convergence of a sequence is not a intrinsic property of the sequence but also depends on the metric space in question. For eg $\{x_n = \frac{1}{n}\}$ is not convergent in $\mathbb{R} \setminus 0$

So we learn that in general, Cauchyness is not sufficient for convergence, but it is indeed necessary:

A convergent sequence is always Cauchy.

Another important theorem is the following:

Let $M$ be a non-empty subset of a metric space $(X,d)$ and let $\overline{M}$ be its closure. Then $$ x \in \overline{M} \iff \text{ there exist a sequence } (x_n) \in M \text{ such that } x_n \to x$$

($\implies$)If $x \in M$, then simply take the sequence $x_n =x$. Otherwise assume $x \in \overline{M} \setminus M$. In this case $x$ is a limit point of $M$. Hence for every $n$, there is an element $x_n \in M$ such that $d(x,x_n) < 1/n$. It can be shown that $x_n \to x$.

($\impliedby$) Given a sequence $(x_n) \in M$ such that $x_n \to x$. If $x_n = x$ for some $n$, then $x \in M \implies x \in \overline{M}$. So we may assume that for all $n$, $x_n \neq x$. Then as $x_n \to x$, for each $\epsilon > 0$, we have a point $x_n \in M$ such that $0 < d(x,x_n) <\epsilon$. Hence $x$ is a limit point of $M$ and thus $x \in \overline{M}$.

Now we know that $M$ is closed if and only if $M = \overline{M}$. Hence the above theorem readily implies the following:

Let $M$ be a non-empty subset of a metric space $(X,d)$ $$ M \text{ is closed } \iff \bigg( \{x_n\} \in M, x_n \to x \implies x \in M \bigg) $$

Question: When is a subspace of a complete metric space complete?

This is an important question and it is addressed in the following theorem:

A subspace $M$ of a complete metric space $(X,d)$ is complete if and only if $M$ is closed.

Let $(X,d)$ be a complete metric space.

($\implies$) Assume that $(M,d) \subseteq (X,d)$ is complete. Now consider a sequence $(x_n) \in M$ such that $x_n \to x$ for some $x \in X$. This is a Cauchy sequence in $M$ and hence it converges in $M$ which implies that $x \in M$. Using the above theorem, we get that $M$ is closed.

($\impliedby$) Assume that $M \subseteq X$ is closed. Consider a Cauchy sequence $(x_n) \in M$. This is also a Cauchy sequence in $X$, and thus $x_n \to x$ for some $x \in X$. But as $M$ is closed, using the above theorem $x \in M$. Thus every Cauchy sequence in $M$ is convergent in $M$, meaning that $(M,d)$ is complete.

Relation between convergent sequences and continuous mappings

We also have the following theorem without proof

Let $(X,d_X)$ and $(Y,d_Y)$ be two metric spaces. Then $$ T:X \to Y \text{ is continuous at } x_0 \iff \bigg( \big(x_n \to x_0\big) \implies \big(Tx_n \to Tx_0\big) \bigg) $$

Chapter-2 Normed Spaces, Banach Spaces

A special case of metric spaces is when the distance metric is defined by the way of a norm. A vector space with a norm defined on it is called a normed space. It automatically defines a distance metric on the space in a natural way. Note that the main difference between is a normed space and a metric space is that in a normed space we have the notion of the length of a single vector/element. This can be naturally extended to a metric by defining $d(x,y) = \norm(x-y)$. In a metric space, we had a metric function defined only for a pair of elements. That is why normed spaces are kind of a special case of metric spaces.

2.1 Vector Spaces

A

vector space over a field $F$ is a set $V$ along with two operations

$+ : V \times V \to V$ and $\cdot : F \times V \to V$ such that:

- For $u,v,w \in V$, some $0 \in V$ and a $v^{-1}$ for each $v$

- $u + v = v + u$

- $u + (v + w) = (u + v) + w$

- $0 + v = v + 0 = v$

- $v + v^{-1} = v^{-1} + v = 0$

- For $a,b \in F$, $u,v \in V$ and $1$ be the multiplicative identity of $F$

- $a(bv) = (ab)v$

- $a(bv) = (ab)v$

- $1v = v$

- $a(u + v) = au + av$

- $(a+b)u = au + bu$

A vector space is a structure which is super useful in a lot of domains. It generalizes the notion of linear combinations, meaning that we have a set of objects on which it makes sense to combine elements in a linear way. This kind of a structure allows for solving of systems of linear equations and much more. Also defining additional structure on it like norms and inner products allow for even more useful operations.

A subspace of a vector space $X$ is a subset $Y$ of $X$ which is itself a vector space. It can be shown that this is equivalent to saying that for each $y_1, y_2 \in Y$ and scalars $a, b \in F$: $$ ay_1 + by_2 \in Y $$

Let $U = \{v_1, v_2, \ldots , v_m\} \subseteq V$ be a finite set of vectors. A linear combination of $U$ is $$ \alpha_1 v_1 + \alpha_2 v_2 + \ldots + \alpha_m v_m $$ for $\alpha_1, \alpha_2, \ldots, \alpha_m \in F$

But there is one important thing to keep in mind regarding linear combinations.

It is important to note that the assumption of finity is inherent in the definition of a linear combination itself. It can never consist of infinitely many vectors. Even if the set $V$ is infinite, a linear combination will always be of only finitely many of those vectors.

Let $M \subset V$. Then the span of $M$ is the set of all linear combinations of $M$.

It can be shown that the span of $M$ forms a subspace of $V$. Infact it is the intersection of all subspaces of $V$ which contain $M$ meaning that it is the smallest subspace of $V$ that contains $M$.

Consider a set of $m$ vectors $(m \geq 1)$, $U = \{v_1, v_2, \ldots , v_m\}$ and the equation: $$ \alpha_1 v_1 + \alpha_2 v_2 + \ldots + \alpha_m v_m = 0 $$ for $\alpha_1, \alpha_2, \ldots, \alpha_m \in F$. This set of vectors is called linearly independent if the only solution of the above equation is $\alpha_i = 0$. It is called linearly dependent if it is not linearly independent.

Note that the above definition only talks about finite sets $U$. We can extend this to an arbitrary set $U$.

Let $U \subseteq V$ be an arbitrary subset. Then $U$ is said to be linearly independent is every non-empty finite subset of $U$ is linearly independent. Likewise, $U$ is called linearly dependent if it is not linearly independent.

A vector space $V$ is finite-dimensional if there exists an integer $n$, such that there is a linearly independent subset of $V$ consisiting of exactly $n$ vectors. Moreover, any set of $n+1$ vectors in $V$ is linearly dependent. It is called infinite-dimensional if it is not finite-dimensional.

A subset $B \subset V$ is called a basis if it is a linearly independent set which spans $V$.

Every vector space $V$ has a basis

This is not hard to show for finite-dimensional vector spaces. For infinite-dimensional spaces, it requires Zorn’s lemma (equivalent to Axiom of choice).

For a given vector space $V$, all basis have the same cardinal number. This is defined as the dimension of $V$.

Let $V$ be an n-dimensional vector space. Then any proper subspace $Y$ of $X$ has dimension less than $n$.

2.2 Normed Space, Banach Space

We have seen metric spaces and vector spaces separately and how metrics may be defined on common vector spaces. But this treatment has not discussed combined treatment of the two, namely we don’t have a geometric notion which fuses with metrics. It turns out there is a way to define a norm on a vector space which generalizes the notion of the length of a single vector (as opposed to metric functions which which took in two vectors as input). This is called a normed space / normed linear space / normed vector space. Also defining a norm very naturally defines a metric on the space too, and this is why normed spaces may be thought of as a special case of metric spaces.

Let $V$ be a vector space defined on the field of $\mathbb{R}$ or $\mathbb{C}$. A

norm is a function $\|\cdot\| : V \to \mathbb{R}$ such that for $u,v \in V$ and $\alpha \in F$:

- $$\|v\| \geq 0$$

- $$ \|v\| = 0 \iff v = 0 $$

- $$\|\alpha v\| = |\alpha| \|v\| $$

- $$ \|u + v\| \leq \|u\| + \|v\| $$

A vector space $V$ with a norm $\| \cdot \|$ defined on it is called a normed space / normed linear space / normed vector space

It can be shown using that axioms for a norm that the following also holds:

$$ \big|\|u\| - \|v\|\big| \leq \|u-v\| $$

Also the following can be shown:

A norm $\|\cdot\|$ is continuous mapping from $V \to \mathbb{R}$

But a metric induced by a norm has some additional constraints. For instance:

A metric $d$ induced by a norm satisfies for $x,y,a \in V$ and $\alpha \in F$:

- $d(x + a,y + a) = d(x,y)$

- $d(\alpha x, \alpha y) = |\alpha| d(x,y) $

This is why all metrics can not be thought of to be derived from a norm.